The Workshop

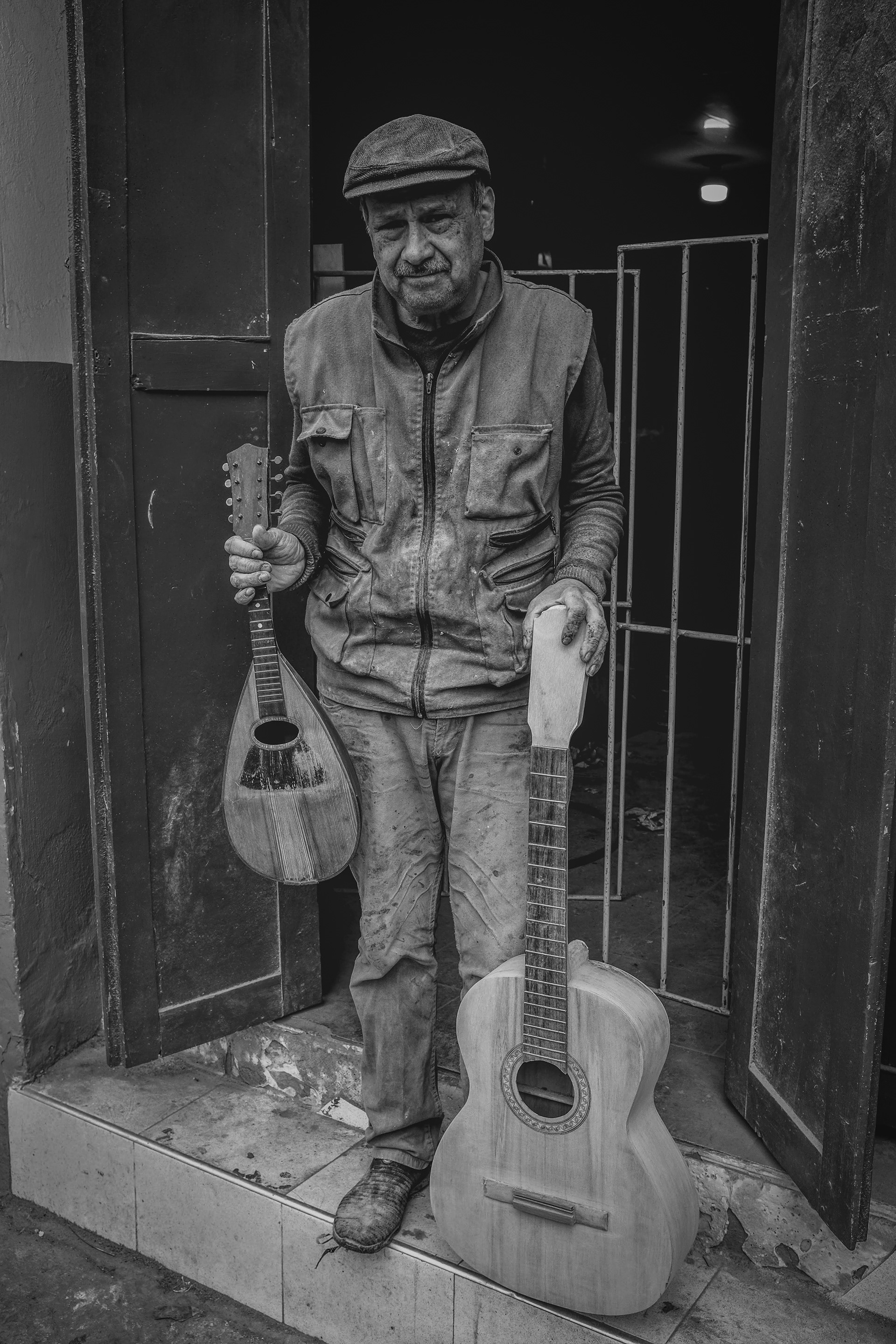

Enrique's shop has been here for more than 150 years. Not this exact configuration of walls and tools, perhaps, but the work itself—the steady transformation of Colombian cedar into tiples, bandolas, requintos, charangos. Enrique Galvis, 66, inherited this corner of La Candelaria from his father, who inherited it from his father, a cabinetmaker who understood wood in the particular way people understood things before generalization took over.

"I've been here since I can remember," Enrique says, running his hand along a piece of cedar in its first stage of becoming. "Since I was a kid, I've been listening to musicians, been in an atelier. This is just what I know."

The workshop smells of sawdust and varnish. Wood in various stages of transformation occupies every surface—raw planks still bearing the geometry of the forest, curved pieces soaking in their molds, instruments nearly complete waiting for their final polish. Enrique picks up what he calls "a piece"—a section of cedar trunk—and traces its journey: from this, to sheets, through the machine for shaping, then the endless process of polishing, sanding, refining. "Keep and keep," he says, using the phrase again and again. "You never finish polishing. The client leaves and you still want to keep polishing."

The Sound of Wood

He knows cedar by color and weight, by how it lets itself be worked. Pink and it's quality. Yellow and it's better for furniture. His father knew more—could identify Catatumbo cedar, Caquetá cedar, Huila cedar by smell and grain. "He knew their names, their smells, everything. I didn't learn that. That's the only thing I forgot." What Enrique did inherit was something deeper: the ability to hear an instrument before it exists, to know what sound sleeps in the wood waiting to be released.

"I know the sound," he says simply. A lifetime of listening will do that.

The Economics of Craft

The economics of luthiery in Colombia are complicated. A guitar that might cost 2,000 dollars in Ecuador or 3,000 euros in Europe sells here for 200,000 or 300,000 pesos—roughly 50 to 75 dollars. "Colombians like to receive things," Enrique says with the particular blend of affection and exasperation reserved for talking about one's own people. "We ask for ñapa, we want a gift, and if we could steal things—better! That's the style of Colombians. We're good for many things, but in certain things, we fail."

He laughs, but the point is serious. The undervaluing of craft work is not unique to Colombia, but here it takes a specific form. Despite this, Enrique has sustained himself for 50 years on this work alone. No pension, no safety net. "What they give me," he says. "Hasta donde me dé"—until it no longer gives.

Finding the Work

He doesn't advertise. No commercial strategy, though he has Facebook and Instagram accounts he considers "bad, perverse things, only for gossip and foolishness, another human stupidity." Instead, people find him the old way: they come to La Candelaria, they hear about the atelier that's been here for more than a century and a half, they climb the stairs and find Enrique surrounded by wood and tools and the patience required to make things properly.

"I make them practically when they ask me to do it, and I'm making it, I'm developing it," he explains. Custom work, each instrument built to order, shaped by conversation and listening. Sometimes tourists buy from him—even Spanish buyers, which amuses him. "No, no, believe that we are not going to be able to do something well because we are Colombians. Not to make me proud, or nonsense like that, but because in reality things can be done well."

The work itself is what matters. When it becomes obligatory, when debts pile up or clients make endless demands, it becomes a straitjacket. But when he's free to work at his own pace, "working the instrument, or the wood as such to make a repair, or restoration—it's very cool, it's very pleasant."

At 66, with no one in his family taking up the craft, Enrique isn't sentimental about legacy. "To any who wants," he says when asked who he's passing his knowledge to. He's taught students, children. "Knowledge stays. It's not only and exclusive to my family."

Keep and Keep

The piece of cedar he showed me at the beginning of the visit will become something extraordinary. You see the stick, he says, then you listen to it, then you hear it being played. "An extraordinary thing." The transformation from forest to music, from raw material to culture, all happening in this workshop that predates the city around it.

Environmental regulations are tightening—necessary and fair to the planet, Enrique acknowledges, but the cedar he bought for 35,000 pesos now costs 50,000, and it will get more expensive. The wood comes

from territories being cleared for cattle, primary forests lost not even for their timber but just to make space. "It loses, it burns, they throw it to the river, and they let it lose."

But for now, there's cedar. There are hands that have done this work for 50 years. There's the machine for shaping, the patience for endless polishing, the ear tuned to recognize what an instrument will become before the first string is stretched across it.

Enrique works without a mask, breathing sawdust, making a joke about cocaine. "Something organic," he laughs. "It's natural, it doesn't have to impact us so much." The lacquer, though—that's chemical, that requires caution. After five decades, he knows the difference.

The workshop continues. The wood keeps arriving, getting scarcer and more expensive but still arriving. And Enrique keeps transforming it, stick by stick, instrument by instrument, in the same space where his father did the same, where someone will hopefully do the same long after Enrique himself is gone.

"People of before understood why and how," he says, thinking about his father's generation, about the specificity of knowledge that's been traded for convenience. But here in La Candelaria, in a workshop more than 150 years old, that understanding persists. In the angle of a saw cut, in the patience of polishing, in the sound that lives in wood waiting to be freed.

Keep and keep. That's the work. That's always been the work.